Targeted sensory reinnervation is a method where a patch of skin is denervated, then reinnervated with nerve fibers from an amputated limb. When this piece of skin is touched, it provides the amputee with the sensation that the missing limb is being touched.

TSR vs TMR (Targeted Muscle Innervation)

One of the key distinctions between these two techniques is the directional flow of information.

TMR enables the brain to trigger muscle contractions in the residual limb (or alternate sites) using nerves that were previously connected to the amputated portion of the limb. The muscle contractions can then be detected by myoelectric sensors and translated into commands for a bionic device.

TSR is used to send information the other way, i.e. back to the brain. By innervating a patch of skin on the residual limb (or alternate sites) with nerves from the missing portion of the limb, and then stimulating that skin, it tricks the brain into thinking it is receiving sensory feedback from the missing limb.

Here is a short video showing how a prosthesis can interact with the reinnervated skin:

And here is a video that provides a good description of the effect of using this TSR in combination with an advanced bionic arm system:

History of TSR

TSR was discovered by accident. During chest surgery, a patient’s chest skin was denervated by the removal of subcutaneous fat. The nerve fibers then regenerated through the pectoral muscle. While receiving an alcohol rub on his chest after the surgery, the patient, an amputee, reported the sensation of being touched on his missing pinky.

This led to an investigation and, ultimately, the development of a surgical technique to purposely restore sensation.

As best we can tell, this original discovery occurred in 2005. However, tracking the development of TSR over time is more difficult than tracking TMR, mainly because there has been less research activity and thus less information.

Comparing TSR to Other Forms of Sensory Feedback

To help you understand the role of TSR, we’re going to walk you through a spectrum of sensory feedback systems (or potential systems), starting with a natural limb. Note, we’re going to use the hand as an example, though most of what we have to say here applies equally to upper and lower limbs. We’re also going to be a little loose with our definitions for the sake of expediency.

A natural limb is wired with both sensory nerves and motor nerves. These ultimately connect to the brain through the spinal cord.

When a person wishes to move a natural limb, the brain transmits signals to the appropriate motor nerves in the limb. The motor nerves cause their associated muscles to contract, which then move the limb.

When a limb makes contact with the outside world (e.g. a hand touches an object), sensor cells on the skin communicate the resulting information to sensory nerves, which in turn pass the information to the brain.

When a limb is severed during amputation, the wiring above the amputation point remains intact. It still has the same capacity to communicate the same level of sensory information to the brain as before. The problem is a) how to obtain that sensory information, and b) how to transmit it to the brain.

Sensory information can be obtained through artificial sensors that can range anywhere from simple pressure sensors to electronic skin.

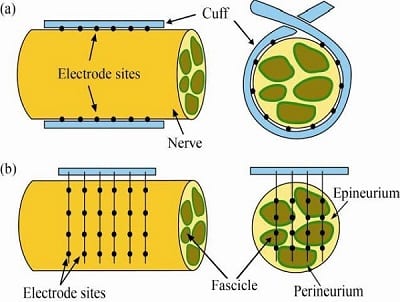

To transmit this information to the brain requires tapping into the remaining portion of the nervous system. The most direct way to do this is by surgically implanting electrodes to electrically stimulate the sensory nerves in a way that tricks the brain into experiencing sensations:

This approach works but has several limitations:

- It involves surgery, with all the inherent cost, pain, and risk of infection.

- It is quite difficult to position the implanted electrodes to communicate precise information. The slightest imprecision might transmit erroneous information. For example, feedback from a bionic forefinger might be interpreted as coming from the pinky instead.

- Over time, scar tissue can form between the electrode/nerve interface, degrading communication.

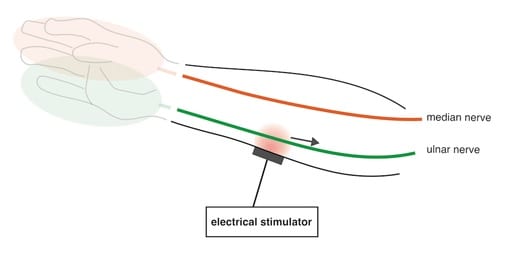

Option # 2 is to attempt to stimulate the nerve through the existing skin using an electrical stimulator. This is known as Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS).

As you can imagine, if directly interfacing with a sensory nerve can be imprecise, trying to communicate with it through intervening skin and tissue can be even more imprecise. As a result, the information that one can communicate through a TENS system is generally much simpler than through an implanted electrode.

TSR provides a middle-ground between these two approaches. By rewiring the skin with the nerves from a missing limb, stimulating that skin can transmit much more complex information without having to wrap or transect those nerves with electrodes. This can potentially solve both the precision and scarring issues.

TSR’s Potential for Phantom-Limb and Neuroma Pain

Unlike TMR and RPNI (Regenerative Peripheral Nerve Interface), which both clearly result in a reduction of phantom-limb pain and painful neuromas for amputees, TSR’s pain-reduction potential is less clear. Some of the early trial surgeries of this technique actually triggered neuroma and phantom-limb pain.

However, in more recent studies, TSR seemed to demonstrate significant potential for pain reduction.

We have no way of resolving this apparent contradiction. We’re mentioning it here to remind you to thoroughly explore this issue with your doctors if you are considering TSR.

Combining TSR and TMR

Earlier, we compared TSR to TMR, but that was just to distinguish between their end goals. In truth, it is far more likely that TMR and TSR will be combined, as they were in the videos at the start of this article.

How Amputees Should Use This Information

As is the case with most of the articles that we write, this article is mainly intended to put this subject on your radar. If you’re interested in TSR, we strongly recommend that you talk to qualified medical personnel as your primary source of information. Unlike with TMR and even RPNI, the information available on the internet is still too incomplete for effective personal research.

Related Information

For a quick summary of all related surgical techniques, see Surgical Techniques That Improve the Use of Bionic Limbs.

For a complete description of all current upper-limb technologies, devices, and research, see A Complete Guide to Bionic Arms & Hands.

For a complete description of all current lower-limb technologies, devices, and research, see A Complete Guide to Bionic Legs & Feet.