An amazing conversation with amputee camp counselor, Richard Slusher. We learned more about limb difference from talking with Richard than we have in nearly a year of hard studying.

Here is our video of this interview:

Although Richard requested that we did not mention his fundraising campaign in the interview, as he wanted to focus on broader issues, this is the one time that we’re not going to listen to him.

If you’re as impressed with Richard as we are, you can help him raise funds for his new bionic arm on his GoFundMe page at https://gf.me/u/y5iug9.

Below, you will find a complete transcript of our interview.

Interview Transcript

Wayne:

Hi Everyone. Welcome to Bionics for Everyone’s first interview in our Real Bionic Stories series.

Today, it’s my pleasure to talk to Richard Slusher who, among many other things, is an Amputee Camp Counselor.

Richard was born missing his right arm below the elbow, and one of the reasons that I wanted to talk to him today is because of the huge dichotomy between the very healthy and productive way that he has embraced his limb difference throughout his life…versus his recent disappointing experience trying to get a new myoelectric arm through his insurance company.

Richard, nice to talk to you.

Richard:

Hi Wayne, it’s great to be with you today.

Wayne:

So, over the past 100 years or so, I think we’ve realized as a society that if we don’t give children with limb differences the support and encouragement they need, they are vulnerable to feeling shy about their differences. And if we’re not careful, they can end up feeling excluded and even isolated.

Can you elaborate a little bit on this?

Richard:

Oh, absolutely, yes. That sense of belonging is extremely important, especially early on in life. I think there’s a number of emotions that children experience when they have a limb difference. That could be uncertainty, a sense of struggle, sadness, and many other things. These are perfectly natural reactions. First and foremost, it’s natural. I think the key is to acknowledge those reactions when they occur and try extremely hard to practice empathy, while also encouraging them to never give up, whatever they do. You’ll find that when you listen to children and support them in a nurturing way, their outlook on themselves, their limb difference, and their future improves greatly.

Wayne:

Now it’s my understanding, from our earlier discussions, that you had that kind of support system growing up.

Richard:

Oh, absolutely, of course. My parents, they didn’t know what to do at first, obviously, besides love their newborn baby. What else can you really do? But once it was absolutely clear that I was healthy, my parents found help and support at Shriners Hospitals for Children in Erie, Pennsylvania. And at that hospital, doctors and occupational therapists went above and beyond to give my parents the tools and information and support they needed for taking care of a baby boy with a limb difference.

The doctors and OT specialists took the time to get to know me, learned my interests, and they accommodated. My dad always had the same attitude. When I was living with him, he always encouraged me to find a way to do something that best accommodates my limb difference. He never forced me to do anything but he also never told me to quit or give up.

And it’s extremely important these early childhood support networks, combined with the encouragement and empathy I received from my family, led to my openness and positive attitude, especially going into school and meeting friends.

Wayne:

It sounds like you had great parents. So were you quite active socially? No problem fitting in with the crowd, as they say?

Richard:

Well, early on, it was a small problem. Kids saw something and someone a little bit different. So who wouldn’t be a little bit hesitant or nervous or confused? And I think that just comes with natural curiosity. But once they saw a kid adapting to his circumstance in a positive way, I was accepted. I think they just needed to see that I could do the same things as they could. As I said, my optimistic personality and my attitude and ability to approach others helped a lot, and that was all due to the support I received at home.

I remember the questions “what happened?” or “what happened to your arm?” or “where’s your arm?” Those questions would always come up to someone new in my life and I would always just spout my rehearsed line, “I was just born that way!” and then immediately I would try to prove myself in a confident way. And in doing so, I feel like I opened the door to many friendships and support from teachers and friends at school. They saw a boy who wasn’t seeking pity or special treatment. I wanted to be held to the same standard as everyone else. And this, I think, was met with great respect and admiration.

Follow Us

Wayne:

And it just goes to show, too, how important it is for the child to be emotionally healthy and supported because that brings it out in you. Now, what about sports? Did you actively participate in sports?

Richard:

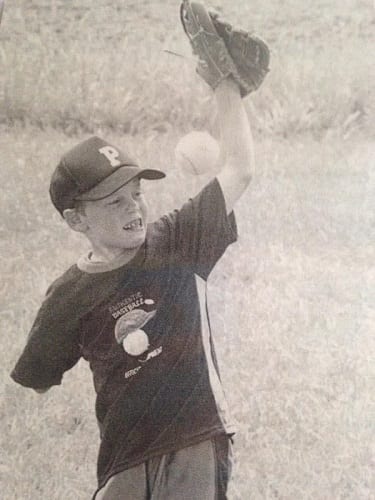

I did. When I was about 8 years old, I got really into baseball and my mom and dad encouraged me to join one of my local little league teams, the Pirates. And, again, any doubt in my ability to hit a ball or throw or catch, that was quickly squashed with my positive attitude and constant practice. And that standard I feel like should be held to any child that joins whatever sports team.

So, I played right field during the games and I had a process. If a fly ball came my way, I’d catch the ball, quickly take off my mitt, stuff the ball into my right armpit, throw down the mitt, and throw the ball back, all in about 3 or 4 seconds. And when I describe that process, and me having one arm on the baseball team, the famous baseball player Jim Abbott comes to mind.

Wayne:

I saw a few documentaries on him and, remarkable guy, so it’s easy to picture what you’re saying about because he was incredible at it. And, to be honest with you, I’m not sure I could catch the ball, take the ball out, and throw it back in 3 seconds, even in my prime, so that’s pretty good. And my prime was a long time ago!

So between having a positive attitude, playing sports, and hanging out with friends, it kind of sounds to me like you had a pretty normal, healthy childhood, and that’s exactly the kind of outcome that we’re looking for kids, whether they’re limb different or not.

Richard:

Absolutely, yes! And it’s all thanks to the support I had along the way. My parents, my friends, my teachers, and my teammates, as well as everyone at Shriners, motivated me and encouraged me at every step of the way. And they listened. When I had doubt, they helped to diminish it. And that’s extremely important to note that they didn’t ignore it. Kids are going to have doubt in their lives, there is absolutely no question. That is especially true for those with limb difference. It’s so important to be heard. Ignoring the doubt or negative emotions that sometimes come with limb difference by blindly pushing a positive mindset is definitely not encouragement. It’s actually quite the opposite. Saying something like, “Hey, I hear you. It’s okay that this upsets you. Let’s work to find a better way and I’ll support you” is so much different than “Well, you’re just not trying hard enough. Don’t be so negative!”

There’s a huge difference in those attitudes. Empathy from your support network is so important to the creation and growth of an outgoing mindset. The support I received was out of empathy and compassion. And this is what I’ve tried to carry with me into adulthood. Through the support I’ve been given, I try to give it back.

Wayne:

Yeah, it’s incredible how strong that vein runs through you. It’s…in talking to you and exchanging emails, you go through this, you get all that support, and, now, the first thing you want to do as an adult is give back and you do that through volunteering as an amputee camp counselor, is that correct?

Richard:

That’s right, that’s right. Oh, this is ten years ago now, back in 2010, I just randomly got a brochure in the mail from Shriners Hospitals in Salt Lake City, Utah. And the brochure advertised an ‘Un-Limb-ited’ amputee camp through Desolation Canyon on the Green River. And this was absolutely a pivotal moment in my life. At that point, I was about 17 years old and I never really interacted with anyone with a limb difference before. I knew how I handled my own limb difference but I was curious to meet others like me and learn their stories and their experiences whether they be positive or negative. I saw it as an amazing opportunity to make new friends, to travel to a new place, to have an adventure.

As a camper, my experience was absolutely eye-opening. I not only learned to better embrace myself and my limb difference, but to further lean on the shoulders of those who faced similar obstacles early in their lives. For those who were facing more difficult experiences with their limb difference or didn’t have the same support that I did, I offered my experience and my empathy, and I believe that in some small way that I’ve helped them. And through those experiences, it led me to return as a camp counselor in 2015 and I remain a counselor to this day.

Wayne:

It sounds like you enjoy working with the kids.

Richard:

I do. I love it. I was able to lean on the shoulders of my counselors and my peers, and I absolutely wanted to offer that in return to someone who may be facing their own doubts or struggling to fit in or having a hard time embracing their limb difference, or just looking to build a support network and learn from someone else.

I’ve gained all that support and self-confidence, but to give it back through the campers I interact with is amazing. I want them to see someone who understands the struggles of limb difference and tries to adapt to them in a positive way. That way, they can, also.

If they leave camp having gained lasting friendships and motivation to buy the dress that shows off their prosthetic leg or finally ask that girl to the prom that they thought maybe they couldn’t do because their limb difference was a barrier. If I can encourage them to do things like that, then I’ve succeeded.

Whatever barriers they thought they faced as someone with a limb difference, my job is to help them break down those barriers and show the world what they’re capable of doing.

Another thing is, I also make it a point to not overindulge in “toxic positivity” or acting like everything is okay. Amputees will face uncertainty and they will face sadness, depression, struggle, and so much more. Those are legit human emotions and it’s okay to not be okay. It’s okay to feel all of those things. I try to make it clear to my campers that those feelings are normal and acting positive all the time can have a strong emotional toll.

Wayne:

You’ve mentioned this a few times now. And it seems to be a really important ingredient to providing this kind of guidance, is avoiding the toxic positivity and giving them the kind of, I guess, I don’t know if the word is “sincere” or “legitimate” or “authentic” guidance. I don’t know which of those words is really the best word but it just strikes me that there’s a difference there between the two different types of guidance.

Richard:

Yes, absolutely. You know, I feel like, in a lot of instances, kids encounter adults in their lives whose job it is to make them feel better or to give them encouragement. But I feel like all too often, it comes off as scripted and that it’s what they have to do and, like you said, you mentioned “authentic”. I feel like, in many cases, kids just don’t feel that it is authentic and that creates a barrier. I mean, if you can’t be real with a kid, if you can’t let them know extremely early on that you empathize with them and that you sincerely care about their experience, you’re not going to get through to them. And that goes for anything. Put Camp aside, that goes for dealing with children in any setting in any form in any circumstance. If you’re unwilling to express authenticity, then that creates such a huge barrier with kids. And that’s something that I’ve seen it before, and it doesn’t work, and I try to be an authentic person, and just going through all of my real experiences and sharing those with the kids and letting them know that, hey, I’ve been through some of these things. I’m not going to fake tell you that, oh, it’ll get better, because honestly sometimes it just doesn’t. And, sometimes, that’s all a kid wants to hear. They want someone to know that someone else knows what it feels like.

Wayne:

Yeah, that makes perfect sense. You have the experience to talk about those things with authenticity. And do you think sometimes, for someone like myself, I don’t have a limb difference, and do you think sometimes it’s a bit of nerves in terms of how to communicate? Like, I sometimes feel a little, and we’re going to get back to this a little bit later, but I sometimes feel a little bit nervous about what is the right thing to say or not say or how to behave, and it’s not, it’s nothing other than the desire to do the right thing but not quite knowing. Do you know what I mean?

Richard:

Right, right, exactly, and, no, you’re absolutely right. There definitely is that sense of awkwardness or stepping on eggshells or people just…I feel like they sincerely don’t want to offend or they don’t want to put those with a limb difference in a bad circumstance. I don’t think they deliberately try to be offending or bring those with limb difference down.

In my experience, it’s all from an area of curiosity but sometimes it just doesn’t come across that way. And I don’t think that’s intentional. I mean, I try to look for the best in all people, and I’ve never dealt with anything extremely negative. It’s not like someone’s ever been like, “Oh, look, he’s got one arm. Ha ha ha. I bet he can’t do this. I bet he can’t do that.” That’s never happened to me. Now, I can’t say that hasn’t happened to anyone else. I’m sure it has and I’m sure it had extremely bad implications, and that’s terrible that some people out there do that, but I feel like the vast majority of people, they want to be respectful and they want to learn and they’re curious but they just don’t know how to go about it in a way that is good for us, if that makes sense.

Wayne:

It makes perfect sense. And we’re going to come back to this issue because it’s kind of central to some of the things we want to talk about. Now, about your prosthesis. Throughout your history and into adulthood, what have you been doing for prosthetics?

Richard:

I was fitted with a cosmetic prosthetic arm when I was a toddler. I don’t really remember using that at all. But I remember asking my mom about that, and she recalls that I did not like it, and I take her at her word.

But she also…she didn’t force me to wear it at any time. She didn’t force me to conform to a standard of how someone should look. She embraced the concept of carrying oneself how they felt was most comfortable. And, you know, I’ll always love her for having that mindset. And I think that is extremely important and it’s helped me into adulthood.

So, during my time in baseball, I found it much easier to play and practice without a prosthetic on. They didn’t allow me to swing the bat as hard as I needed to. They also didn’t help with catching or throwing the ball. So, to swing the bat, I just held the bat with my left hand and rested my stump on it, too, and that was just the most comfortable and strongest way to go about it.

But, nevertheless, as I grew, prosthetists at Green Prosthetics & Orthotics, which is also in Erie, PA, helped me every step of the way in fitting me with body-powered prosthetic limbs, which is what I used after the cosmetic hand, and what I sometimes use today, too.

Wayne:

And how is that, using the body-powered prosthesis?

Richard:

Ah, well, the body-powered prosthesis has a hand that looks like a normal, skin-toned hand. This type of arm is pretty heavy and it’s limited in its grasping abilities, which is controlled by a shoulder strap. I can bring it into focus here so the viewers can get a look at it.

So this is the body-powered prosthetic arm. I can get the hand close to the screen there and you can tell that the two fingers and the thumb are basically what is gripping, but it’s very precise. When I extend my stump, it pulls the string on the harness, which closes the thumb into the index and the middle finger.

Depending on how often I use it, my armpit gets sore and sometimes I get a rash because of the straps rubbing against my skin. Sometimes, I fix this by wearing an extra shirt but, especially in the summertime, that gets really hot and it’s just an inconvenience. Who wants to wear two shirts if it’s not cold outside.

Wayne:

Yeah, also, sorry to interrupt there for a second, but there are also some long-term implications to using body-powered because there’s a motion that you’re doing that’s not exactly a natural motion, right?

Richard:

That’s right, that’s right. I’m not an expert on what that does long-term by any means but I’m certain it’s not good. And, another thing, since you brought up implications on the body and long-term effects, every once in a while I find myself leaning my right shoulder down just because, when I’m wearing the body-powered arm, it feels like it’s just kind of hanging there and not helping me do anything, so, every once in awhile, I don’t give it the support that it needs so my shoulder’s kind of slugging a little bit. And that’s not good for posture and it doesn’t look good to boot.

Wayne:

I’m no expert, either, but there are also long-term health implications to this. I mean, you’re still young, so maybe you wouldn’t notice it yet, but they are there.

So you had that device for a while, and then you went on, at some point, did you, to a myoelectric?

Richard:

Yes, about, oh, seven years ago, I had the opportunity to get fitted with a myoelectric prosthesis called the MyoFacil from Ottobock.

Wayne:

And that was your first myoelectric arm?

Richard:

That’s right. Up until this point, I had never used one. The body-powered arm was all that I had.

Wayne:

And how was that, especially the difference between the two?

Richard:

Oh, well, I wouldn’t be honest if I told you that it wasn’t a huge step in the right direction at first. It definitely allowed me to use a prosthesis in a way that I hadn’t been able to with the previous one. I could use my muscles in my stump that I didn’t even know I had. I remember the doctors telling me, “okay, well, we’re going to test you to see if you can use this kind of prosthesis”. Then they said, “start flexing your stump muscles”, and I’m like, well, I didn’t even know I had muscles there. So I spent a few weeks just learning how to flex those muscles, which was amazing when you discover muscles on your body that you didn’t even know that you had. That’s definitely exciting. So I learned how to use those muscles to open and close the hand and rotate the wrist. And, for once, it felt like I had an actual hand and arm.

But, over time, as I got older, my views began to change. It’s still…I have it right here:

It’s still a skin-toned hand and I don’t like that anymore. I began to resent the feeling of conformity, the idea of wearing an arm that looks like a real hand, as if it’s what I need to look like. It’s also a lot heavier than the body-powered arm and it becomes extremely tiring to wear for long periods of time. Not only that but prolonged use of it causes irritation on my stump due to the really, really tight fit in the socket that’s needed to operate the electrodes properly.

If I’m wearing it and I don’t feel like it’s really, really tight, it just feels like it’s going to fall off. The same goes in hot weather. If I start to sweat, even just a little bit, in the summertime, it just feels like it’s going to fall right off.

Wayne:

It’s a very common problem and, sometimes, that sweating will affect the sensors so they don’t work.

Richard:

That’s right, yes. Another thing, the grips are very basic. The hand opens and closes, though a lot of things just don’t fit in the hand to hold it efficiently or safely like certain coffee thermoses because I’m an avid coffee drinker.

Wayne:

You, too, eh?

Richard:

Yeah, I have to have my coffee to function in the morning and if I’m going out to work and I put my coffee in a to-go cup, it just doesn’t fit, so that’s a problem.

It’s definitely not weight-bearing, the batteries only last for so long…the batteries…so let’s just say I’ve locked myself onto a shopping cart or two. That gets pretty embarrassing being locked to a shopping cart.

Wayne:

Yeah because the hand just seizes up, right, in the position that it’s in?

Richard:

That’s correct.

Wayne:

Now as I understand it, that arm is now 7 years old, which means that’s at the end of its lifespan, so, of course, you’re looking to find a replacement, and Open Bionics’ Hero Arm has caught your eye.

Richard:

That’s right. I’m always on the lookout for advanced bionic limbs, just because I think the technology is amazing, which just fascinates me. The Hero Arm was something I found in promotional videos just searching on YouTube. Specifically, I found a video of Tilly Lockey in her promotion of one of the films that was coming out at the time, and she was using the Hero Arm to promote that. And it was just amazing seeing her use it with such ease and excitement and empowerment.

Wayne:

Yeah, she’s a remarkable young woman and she’s also an inspiration for our site, actually, at bionicsforeveryone.com. Just so people understand what we’re talking about, I’m going to put up a short montage of the Hero Arm here on the screen, and you can see for yourself:

That was obviously a commercial, not a montage, which I swapped in while editing this interview. But you can clearly see the appeal of the Hero Arm.

Now a lot of people don’t understand the true implications of this arm, but we just did an entire article on this subject. I don’t know if you got a chance to see that — the article we just did on The Revolution in Prosthetic Aesthetics — so I’m going to elaborate a bit here. Yes, this arm is the next step in the technology evolution of bionic arms. It’s a full generational upgrade over the MyoFacil — the one that you showed us earlier.

But what’s really revolutionary about the Hero Arm, as you can see, is its sleek, ultra-cool, ultra-hi-tech appearance. And why does this matter? Well, this gets us back to some of the points you’ve already raised. Because it turns out that those with limb differences don’t want to feel shy about those differences. They have a very deep emotional desire — this is what I’ve been reading through that interview — to embrace their differences, to be proud of their prosthesis, and to turn it into something to admire that they can use to express themselves. Now is this part of the Hero Arm’s appeal to you?

Richard:

To be completely honest, that’s probably the most appealing part about it. I sound like a broken record but I’ve used really basic-looking, skin-toned limbs my whole life. And just to reiterate, I’ve evolved from the mindset of conformity when it comes to wearing a prosthesis. I understand that skin-toned limbs work for some people, and that’s completely fine! I’m not trying to discourage anyone else out there who wants to embrace a skin-toned limb. If you do, that’s completely awesome and you should go for it. But that’s not what I want.

Why? Because I don’t want to be put into a box when it comes to my limb difference. I don’t want to conform to the mindset of “this is what you have to look like”. And the Hero Arm is unique in its appearance. It’s Star Wars, it’s Iron Man, it’s the Terminator. It’s your favorite color. It lets your true personality shine through. In wearing the Hero Arm, I feel I can fully break free of conformity and let my personality just run wild. I can express myself in an adaptive way.

Wayne:

You know, it’s unbelievable how strong this sentiment is. In this article I was telling you about, we did half the article on the Hero Arm and half the article on these Limb-Art leg covers for prosthetic legs, and it’s just endless — the quotes from people and how passionate they are about being able to express themselves. It was really an eye-opener for me.

Now it also turns out — and this is something nobody really predicted other than the Open Bionics CEO, Joel Gibbard — is that attractive, super cool prosthetics also have a huge impact on those who don’t have limb differences.

I’m not going to get too deep into this because, as I said, we cover it in-depth in our article, but let me explain briefly what I mean.

We mentioned earlier about how sometimes it can feel a little bit awkward — those of us who don’t have limb differences get a little bit nervous about what to say or what not to say.

I’m not talking about ableism here. I’m talking about a situation where…let me give you an example, a handshake scenario. So, you approach somebody who is wearing a prosthesis and you’re not really sure which hand to use. The uncertainty comes from, maybe they want to shake hands with their prosthesis, in which case, of course, you want to shake hands with their prosthesis. But maybe they don’t want to shake hands with their prosthesis and you don’t know. So there’s that moment, and it’s just kind of a moment of uncertainty where you’re kind of looking for some kind of signal about what’s right or what’s not, and this is what leads to this awkwardness. But when somebody has a really cool prosthetic, this is what the facts are showing, others are reacting really enthusiastically to it. People will just naturally say something like, “cool hand” or “cool leg” with the leg covers, and this serves to break the ice and, according to all the interviews I did for that article I was referring to, all the awkwardness is just evaporating on the spot. And it’s just kind of occurring naturally. I assume that this is also part of the appeal to you?

Richard:

Oh, yes, absolutely! And your point about the hand-shaking is all too familiar. I extend my left hand to a right-handed shaker all the time to avoid the awkwardness of my body-powered prosthesis or my myoelectric one. And sometimes that leads to even more awkwardness due to an abnormal handshake, you know, if you put out the wrong hand, obviously, aside from the face, a handshake is probably one of the best first impressions that you get from somebody. And I don’t have the enthusiasm for wearing these arms to put that on display for others in a handshake.

But since the Hero Arm is a much cooler and advanced limb, with customizable covers and whatnot, I feel I’d be extending it to every person who I came into contact with simply out of pure excitement. Instead of someone noticing a prosthesis that kind of looks like a normal arm and being nervous about offending me, they’ll see an awesome robotic arm and want to learn more about it! With the Hero Arm, it won’t be “Hey, oh, he’s got a fake hand, that’s weird.” But rather “Oh, he’s got a robotic hand! That’s so sweet! I want to learn more about that!”

Wayne:

Yeah, you know, I’m a tech junky, like so many of us are nowadays, and I honestly would be the same way. All the awkwardness would go out of it for me. I’d probably want to grab the bionic hand and shake it, just because I’d go, “Man, that’s cool.” And it is really cool.

So your existing myoelectric arm is nearing the end of its lifespan. You’ve found this fantastic new myoelectric arm which, by the way, as you’re aware from online and stuff, it’s received rave reviews. It’s changed at least hundreds if not thousands of lives at this point. And you’re working now, so you have insurance coverage. And the arm isn’t outrageously expensive, by the way, compared to the 60, 70, 80 thousand dollars it used to cost. It’s about $20,000 US, between $15,000 and $20,000, all included, which, considering that it will last you 5 to 7 years, we’re starting to get the costs down to a pretty low cost-per-year.

But you don’t have that kind of money to lay out. 17 grand is a lot of cash. So you call your insurance to find out if they can help you with the purchase, and what happens to you next?

Richard:

Oh, boy, so this was a process. I inquired with my insurance company about the kinds of prosthetic coverage options that would have been available under the company I’m with, and I got a lot of unclear and contradicting answers, even dodges to some of my questions.

First, I was told that prosthetic limbs fall under Durable Medical Equipment, or DME, and I kind of already knew that at the time, but I didn’t have that in my plan to begin with, so I was kind of on a mission to see if I could get that in my plan. So that was my first task — to inquire about the DME coverage. Then I was told by another representative that, no, it’s not considered DME. It’s something else.

So I humored them. I’m like, oh, okay, if it’s not DME, what do you consider it because, I don’t know, maybe different insurance companies have prosthetic devices under a different umbrella. I mean, I don’t know the insurance terms but maybe to X insurance company, it’s DME. Maybe to Y insurance company, it’s something else. I don’t know.

But after multiple attempts to find out what prosthetic limbs fall under if not DME, I was just told two or three times that it wasn’t DME, and I’m, like, okay, I realize that. What is it, though?

And, finally, I was told that it falls under physical therapy and that kind of sounded odd. So, that was a bit discouraging. Then, after that, I was told that prosthetic limb coverage just isn’t available. And I’m like, okay, well, first, you tell me that it’s under Physical Therapy and now you’re telling me it’s not available at all? What’s your angle here? So that was confusing. And just the constant jumping through hoops and not getting clear answers was extremely stressful and so disappointing because it just, at the end, it became clear to me that they didn’t want to offer any assistance to me at all.

Wayne:

Yeah, and it wasn’t just the fact that you got a no, but it’s kind of an indifferent, disinterested, quite frankly it’s like a disrespectful no, like they don’t care. They’re just searching for an excuse.

Richard:

Yeah, like I didn’t even matter. Like they just wanted to find any reason that they could to reject my inquiries. They didn’t care how many times they bounced me around or gave me vague, unhelpful answers. It just turned me completely off the insurance route.

Wayne:

Yeah, by the way, you’re not alone there. I happened to read all the insurance policies and a bunch of other…it’s just terrible, the wording, the complicated perspectives, the different standards by which they judge whether they approve something or don’t approve something. It’s really kind of a miserable situation.

So what other options are available to help you get this arm?

Richard:

Well, the government can’t help me because I don’t qualify for Medicaid or Medicare. I work, obviously. I have bills to pay and ends to meet. I’m not trying to get too political here but the United States healthcare system really is not out to make the lives of those with limb differences more efficient. So there’s really no other viable option but to raise the funds, which I’m trying to do online right now. But that’s not the main reason I’m sharing my story. There’s something much, much bigger at stake.

Wayne:

What do you mean by that?

Richard:

Well, I’m going to get the Hero Arm one way or the other. If I can’t raise the funds online, then I’ll look for alternative means. I’ll try and get an extra job. I’ll borrow the money or some other means. But the one thing that I’m not going to do is go away with my tail between my legs. That’s definitely not the example I want to set for other young amputees out there, and especially those at camp.

But think about all those kids just for a minute. If I feel a strong desire to have the Hero Arm, imagine how much they’re going to want one. And if I can be upset because the world places barriers in my path to getting the Hero Arm, how much more upset will some of them will feel as image-conscious teens? It’s like we’ve created this perfect prosthesis for them. We’re dangling in front of their noses in the press and on YouTube, and then we’re going to tell them that they can’t have one because neither the government nor the insurance industry wants to help pay for them? That’s devastating and, in my view, a violation of basic human rights.

Also, think about what’s going to happen to kids from lower-income families. If we don’t figure out a way to get modern prosthetics to those who need them, regardless of their economic status, we’re going to end up creating different classes of those with limb-difference.

We could have a scenario where two kids with limb difference end up in the same classroom. One has this super cool, hi-tech, modern prosthesis that gets all this positive attention and helps him or her fit in, while, on the other hand, you’ve got this kid that has an older, passive prosthesis the other kid has this old, passive prosthesis that they’re trying to hide.

In situations where we’re trying to instill confidence in these kids, this is an absolute nightmare scenario.

Wayne:

Oh, it is. It’s an unbelievable situation. I mean, I’m so aware of the impact…like I said, we just did this article on the Hero Arm…but listening to the kids, watching the videos, listening to the parents talk, going online listening to people talk…I mean, this thing has such a huge impact, positive emotional impact on kids. The dichotomy between that and then blocking the kid from getting that, it’s just like…I mean, I imagine how you feel about it because, even to me, it’s like a stab in the gut, like, oh my God, are we going to really do that to these kids? Or to anybody, really.

So what can we or should we be doing about this?

Richard:

Well, we have to provide everyone with a limb difference the tools they need not only to live adaptively but to encourage positive emotional and physical growth. We need to really listen to these kids’ needs and empathize with them. These decisions on how we live our lives, they just can’t be decided by a committee of able-bodied people. Each and every person deserves access to the absolute best in prosthetic devices. Not only does it affect emotional development but it has lasting effects on the human body, like you mentioned earlier.

For me, I’ve started to get vocal about these issues and these rights. Shriners and Green provided my prosthetic limbs for free until I was 21 years old, then I was on my own. Since having to navigate the insurance world, I’ve learned just how discouraging and daunting the process can be for amputees, young or old. And it absolutely should not be this way. If someone needs a prosthetic leg that tailors to their specific amputation, they should get it, not be confined to a wheelchair. They have the human rights to be able to walk. If someone needs a prosthetic arm that better helps them tie their shoes or cut food in the kitchen, they should get it, not face lasting back pain or risk injury in the kitchen.

I mean, this is not rocket science.

Wayne:

It’s so basic.

Richard:

It is. So, there are many organizations that are helping to spread awareness. Amputee Coalition is a really big one and I’ve found myself taking advantage of their resources and their guidance. The main solution is for the limb-difference community to unite and demand the rights that they deserve. There are support networks everywhere, much like what I had as a child, and we need to seek them out and capitalize on them.

Wayne:

I can’t argue with a single word you’ve said.

You’ve been through the experience of having a limb difference as a child. You know what it’s like to have a healthy outcome. You’re the perfect person, in that way, in that you’ve had the experience, you’ve had the support, you’ve been a camp counselor. You can clearly see the distinction between when we do it right and when we do it wrong. Doing it right would be to provide everybody with a prosthesis or prosthetics that they need. And doing it wrong would be to block them for what is, from a healthcare standpoint, really not a lot of money anymore. It’s just ridiculous.

And you’ve put your money where your mouth is. That’s the other thing about you. It’s not just the knowledge. Like, you didn’t have to go back to camp and become a camp counselor. You do that, you devote your time and your effort to help kids, and you sound like exactly the kind of person that we should be listening to.

Richard:

Not only me but everyone else who is active in the limb different community. Our voice and our health absolutely matters. We know what to do to help. The frustrating part is that we don’t have the power. We don’t have much of a say in national health programs. We don’t have much of a say in the insurance industry. It’s big and it’s powerful, and it’s out to make money. And that has to change. You cant’ expect these people who hold our lives in their hands to empathize with someone who lives with limb difference or any other disability, for that matter, when they don’t live it themselves.

Wayne:

That’s so true. Look, I’ve spent the past year learning everything I can about limb difference and other forms of what we mistakenly often call disabilities, and as much as I’ve learned, there’s no way that I can ever understand the issue like you do. It’s impossible. We have to put the power in the hands of the people who really know what they’re talking about because despite all the effort I’ve put into learning, despite my really good intentions, I just simply wouldn’t know what the right thing to do was. I wouldn’t know.

I have to say, you’re a pretty inspiring guy. And I know you asked us not to promote your fundraiser in this interview, but I think that…I want those kids that you mentor to see that anything is possible, too. I do want to see that because that inspiration that comes out of you goes into those kids and we should do what we can to help it.

So for those watching this video, I say let’s give Richard a hand…a bionic hand, to be specific. Let’s make sure that when he goes back to camp, he’s showing the kids his new Hero Arm and he’s inspiring them to get the prosthesis that they need, regardless what happens and regardless of what obstacles are put in front of them.

And, Richard, please come back to talk to us again anytime you have something you want to share on the subject of limb difference or bionics, for that matter.

And maybe you can come back once you get your Hero Arm and tell us the kind of difference it’s made to your life so that people can better understand why it’s so important that we get these advanced devices into the hands of the people that need them.

Richard:

Absolutely, absolutely. Thank you so much, Wayne. I appreciate your time. I appreciate your support. And you’ll definitely be hearing from me again. A limb difference advocates work is never done!

Wayne:

That was really great talking to Richard. In the few conversations I’ve had with him, I think I’ve learned more about limb difference than I have in the entire past year.

Now a couple of contact notes. If you would like to get in touch with Richard, you can do so at the following addresses:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/BionicSlusher

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/lucas.slusher

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/richardlucasslusher/

Most importantly, you can help him get his Hero Arm by chipping in a few dollars at his GoFundMe page at: https://gf.me/u/y5iug9.

Finally, you can always reach us at: bionicsforeveryone.com.

Thanks for watching our first Real Bionics Stories video, and I hope you’ll come back for more.

Related Information

For more information on the Hero Arm, see Open Bionics Hero Arm.

For a comprehensive description of all current upper-limb technologies, devices, and research, see our complete guide.