A recent study suggests that the adult human brain is incapable of adjusting its sensory map to match the location of bionic sensors. This may make it more difficult to obtain precise sensory feedback from bionic hands.

The Plan

The human brain retains a sensory map of amputated limbs. When the brain attempts to move a missing limb, it still sends signals to any relevant nerves. Intercepting these signals and translating them into commands is the basis for bionic arm/hand user control systems.

However, this isn’t a one-way system. Electrically stimulating a nerve can send information back to the brain, fooling it into believing it has touched something with the missing limb. This is the basis for true sensory feedback.

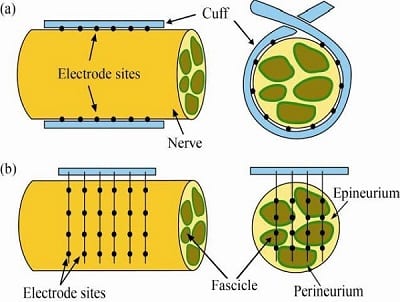

The most sophisticated way to stimulate a nerve is to surgically connect an electrode to it, otherwise known as a neural interface.

In a perfect world, the stimulation would directly mimic the sensory experiences of a bionic device. Touch your bionic thumb and your brain is tricked into thinking that you have touched your natural thumb.

At least that’s the plan!

The Problem

It is quite difficult for surgeons to implant electrodes for precise communication with a nerve. If the position of the electrode is off even slightly, it can result in imprecise stimulation. If you touch your bionic thumb, it may feel as if you have touched another finger instead.

This could be highly problematic if the purpose of the feedback is to improve user control over individual digits.

Scientists had hoped that repeated visual cues about the correct touchpoint would eventually help the brain adjust its sensory map. Unfortunately, this doesn’t seem to be the case:

This diagram represents the results of a study titled “Use of a Sensitized Bionic Hand Does Not Remap the Sense of Touch” 1. In this study, three participants received stimulation from a bionic thumb through an implanted electrode. The perceived location of the stimulation differed from the actual touchpoint.

Despite using their bionic hands continuously for up to three years, none of the participants experienced any adjustment to their sensory maps. Stimulation applied to the thumb continued to be perceived at other locations even though there were repeated, long-term cues that this was not correct, such as visual awareness that the thumb was the true contact point.

The sensory map of an adult brain appears to be quite rigid.

The Implications

What can bionic hand users learn from this study?

Non-invasive sensory feedback systems using vibration already exist but they’re both simplistic and non-intuitive. That is, the brain doesn’t experience the actual sensation experienced by the bionic fingers. Instead, it must learn to equate vibration to contact and the strength of that vibration to the grip force being used.

More recently, efforts have been made to use transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for non-invasive feedback. In this model, a bionic finger passes sensory input to a control system, which then causes a surface electrode to send an electrical charge through the skin to the target nerve. This stimulation of the nerve is intended to cause the brain to experience something representative of the original sensory input. However, as you might expect when trying to pass information through intervening tissue, the “messages” have to be relatively simple. Using current technology, they cannot represent complex sensory feedback such as texture, shape, etc.

These limitations are what have caused scientists to explore more direct interaction with nerves, i.e. an invasive neural interface. However, the only reason to undergo the added expense and risks (scarring, infection, etc.) of surgery is to improve the accuracy and sophistication of the feedback system. If the system can’t do this with sufficient precision, it defeats its own purpose.

Our verdict? Not every neural interface will be identical to the type referenced in this article. New advances are occurring all the time. But if you are considering having electrodes surgically implanted to improve sensory feedback, you should thoroughly discuss this issue of precision with your doctor, especially for use with a bionic hand.

Related Information

Click here for more information on advanced neural interfaces for bionic hands.

For information on sensory feedback, please see Sensory Feedback for Bionic Hands, Sensory Feedback for Bionic Feet, and Understanding Bionic Touch.

For a comprehensive description of all current upper-limb technologies, devices, and research, see A Complete Guide to Bionic Arms & Hands.

References

[1] Ortiz-Catalan, Max & Mastinu, Enzo & Greenspon, Charles & Bensmaia, Sliman. (2020). Chronic Use of a Sensitized Bionic Hand Does Not Remap the Sense of Touch. Cell Reports. 33. 108539. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108539.